Battle of the Kasserine Pass

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

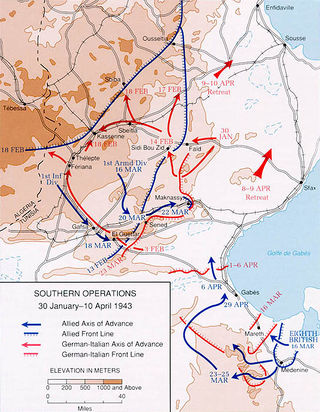

The Battle of the Kasserine Pass took place in World War II, during the Tunisia Campaign. It was, in fact, a series of battles fought around Kasserine Pass, a two-mile (3 km) wide gap in the Grand Dorsal chain of the Atlas Mountains in west central Tunisia. The Axis forces involved were primarily from the German-Italian Panzer Army (the redesignated German Panzer Army Africa) led by Field Marshal Erwin Rommel and two Panzer divisions attached from the Fifth Panzer Army. The Allied forces involved came mostly from the U.S. Army's II Corps commanded by Major General Lloyd Fredendall, which was part of the British First Army commanded by Lieutenant-General Kenneth Anderson.

Significant as the first large-scale meeting of American and German forces in World War II, the untested and poorly-led American troops suffered heavy casualties and were pushed back over fifty miles (80 km) from their positions west of Faid Pass in a rout. In the aftermath, the U.S. Army instituted sweeping changes from unit-level organization to the replacing of commanders. When they next met, in some cases only weeks later, the U.S. forces were considerably more effective.

Contents |

Background

American and British forces landed at several points along the coast of French Morocco and Algeria on November 8, 1942, during Operation Torch. This came only days after General Bernard Montgomery's breakout in the east following the Second Battle of El Alamein. Understanding the danger of a two-front war, German and Italian troops were ferried in from Sicily to occupy Tunisia, one of the few easily defended areas of North Africa, and only one night's sail from bases in Sicily. This short passage made it very difficult for Allied naval vessels to intercept Axis transports, while air interdiction proved equally difficult while the nearest Allied airbase to Tunisia, at Malta, was over 200 miles (320 km) distant. As the Allied build-up after Torch continued, more aircraft became available and new airfields in eastern Algeria and Tunisia became operational, resulting in greater success in stopping the flow of men and equipment into Tunis and Bizerta. But by this time, sizeable forces had already come ashore.

An attempt was made to cut off Tunis in November and December 1942 before the German troops could arrive in strength. However, because of the poor road and rail communications, only a small (divisional size) force could be logistically supported and the excellent defensive terrain allowed the small numbers of German and Italian troops landed there to hold them off.

On January 23, 1943, Montgomery's Eighth Army took Tripoli, thereby cutting off Rommel's main supply base. Rommel had planned for this eventuality, intending to block the southern approach to Tunisia from Tripoli by occupying an extensive set of defensive works known as the Mareth Line, which the French had constructed in order to fend off an Italian attack from Libya. With their lines steadied by the Atlas Mountains on the west and Gulf of Sidra on the east, even small numbers of German/Italian troops would be able to hold off the Allied forces.

Faïd

Upsetting this plan was the fact that Allied troops had already crossed the Atlas Mountains and had set up a forward base of operations at Faïd, in the foothills on the eastern arm of the mountains. This put them in an excellent position to thrust east to the coast and cut off Rommel's forces in southern Tunisia from the forces further north, and cut his line of supply to Tunis.

Elements of von Arnim's Fifth Panzer Army reached the Allied positions on the eastern foot of the Atlas Mountains on January 30. The 21st Panzer Division met French troops at Faïd and despite excellent use of the French 75 mm guns, which occasionally caused heavy casualties among the German infantry,[nb 1] the defenders were easily forced back. U.S. artillery and tanks of the 1st Armored Division then entered the battle, destroying some enemy tanks and forcing the remainder into what appeared to be a headlong retreat.[3]

In reality, U.S. armored forces had fallen victim to an old German tactic, previously employed with much success against British forces. The German tank retirement was a ploy, and when the panzers reached their old positions, with U.S. armor in hot pursuit, a screen of German anti-tank guns opened up, destroying nearly all the American tanks. A US forward artillery observer whose radio and landlines had been destroyed by shellfire recalled, "It was murder. They rolled right into the muzzles of the concealed eighty-eights and all I could do was stand by and watch tank after tank blown to bits or burst into flames or just stop, wrecked. Those in the rear tried to turn back but the eighty-eights seemed to be everywhere."[3] Now unopposed by armor, the 21st resumed its advance towards Faïd.[3] During the German advance, American infantry casualties were exacerbated by the American habit of digging shallow slit trenches instead of foxholes, as German tank drivers could easily crush a man inside a trench by simply driving into it and simultaneously making a half-turn.[4]

Several attempts were made by the U.S. 1st Armored Division to stop their advance, but all three combat commands found themselves faced with the classic blitzkrieg; every time they were ordered to defend a position, they would find that it had already been overrun, and they were attacked by German troops with heavy losses.[3] After three days, the U.S. II Corps was compelled to withdraw into the foothills.

Most of Tunisia fell into German hands, and the entrances into the coastal lowlands were all blocked. The Allies still held the interior of the roughly triangular Atlas range, but this seemed of little concern to Rommel since the exits eastward were all blocked. For the next two weeks, Rommel and the Axis commanders further north debated what to do next. Given his later actions, this delay may have proven costly.

Sidi Bou Zid

Rommel eventually decided that he could improve his supply situation and further erode the American threat to his flank by attacking towards two U.S. supply bases just to the west of the western arm of the mountains in Algeria. Although he had little interest in holding the mountains' interior plains, a quick thrust could capture the supplies, as well as further disrupt any U.S. actions.

On February 14, the 10th and 21st Panzer Divisions attacked Sidi Bou Zid, about 10 miles (16 km) west of Faïd in the interior plain of the Atlas Mountains. The battle raged for a day, but the U.S. armor was outmatched and the infantry, poorly sited on three hills and unable to give mutual support, was isolated. By the end of the day, the field was won by the 5th Panzer Army. A counterattack the next day was beaten off with ease, and on February 16, the Germans started forward again to take Sbeitla.

With no defensive terrain left, the U.S. forces retreated to set up new lines at the more easily defended Kasserine and Sbiba Passes on the western arm of the mountains. By this point, the U.S. forces had lost 2,546 men, 103 tanks, 280 vehicles, 18 field guns, 3 antitank guns, and an entire antiaircraft battery.

Axis plan

At this point, there was some argument in the Axis camp about what to do next; all of Tunisia was under Axis control, and there was little to do until the Eighth Army arrived at Mareth. Eventually Rommel decided his next course of action should be to attack through the Kasserine Pass into US II Corps' main strength at Tébessa. In this way, he could gain vital supplies from U.S. dumps on the Algerian side of the western arm of the mountains, eliminate the Allies' ability to attack the coastal corridor linking Mareth and Tunis, while at the same time threatening the southern flank of First Army. On February 18, Rommel submitted his proposals to Kesselring, who forwarded them with his blessing to the Comando Supremo in Rome.[5]

At 13.30 on February 19, Rommel received the Comando Supremo's agreement to a revised plan. He was to have 10th and 21st Panzer Divisions transferred from von Arnim's 5th Panzer Army to his command and attack through the Kasserine and Sbiba passes towards Thala and Le Kef to the north, clearing the Western Dorsale and threatening the First Army's flank.[6] Rommel was appalled. This plan diluted the concentration of his forces and would, once through the passes, dangerously expose his flanks. A concentrated attack on Tébessa, while entailing some risk, could yield badly needed supplies, destroy Allied potential for operations into central Tunisia and possibly give the Luftwaffe a forward base in the form of the airfield at Youks-les-Bains to the west of Tébessa.[7]

Battle

On February 19, Rommel launched an assault. The next day, he personally led the attack by Kampfgruppe von Broich a battlegroup from the 10th Panzer Division, lent to him from von Arnim's Fifth Panzer Army to the north,[nb 2] hoping to take the supply dumps, while the 21st Panzer Division, also detached from the Fifth Panzer Army, continued attacking northward through the Sbiba gap.

Within minutes, the U.S. lines were broken. Their light guns and tanks had no chance against the heavier German equipment, and they had little or no experience in armored warfare. The German Panzer IVs and Tiger tanks fended off all attacks with ease; the M3 Lee and M3 Stuart tanks they faced were inferior in firepower and their crews far less experienced. Rommel had special words of praise for the 7th Bersaglieri Regiment, who attacked fiercely and whose commanding officer, Colonel Luigi Bonfatti, was killed during the attack.[9]

Under fierce tank attack, the American units on Highway 13 also gave way during the night, with men at all points retreating before the Italian 131 Armoured Division Centauro.[10] Meanwhile, U.S. commanders radioed higher command for permission to arrange a counterattack or artillery barrage, often receiving a go-ahead after the lines had already passed them. Once again, the 1st Armored Division found itself ordered into useless positions, and by the second day of the offensive, two of their three combat commands had been mauled, while the third was generally out of action.

After breaking into the pass, the German forces divided into two groups, each advancing up one of the two roads leading out of the pass to the northwest. Rommel stayed with the main group of the 10th Panzer Division on the northern of the two roads towards Thala, while a composite Italian-German force supported by tanks of the Italian Centauro Armoured Division took the southern road toward Haidra. To combat the southern force, the remaining Combat Command B of the 1st Armored drove 20 miles (30 km) to face it on February 20, but found itself unable to stop the advance the next day.

Morale among the U.S. troops started to fall precipitously, and by evening, many troops had pulled back, leaving their equipment on the field. The pass was completely open, and it appeared the supply dump at Tébessa was within reach. However, desperate resistance by isolated groups left behind in the action seriously slowed the German advance, and on the second day, mopping up operations were still underway while the armored spearhead advanced up the roads.

By the night of February 21, the 10th Panzer Division was just outside the small town of Thala, with two road links to Tébessa. If the town fell and the German division decided to move on the southernmost of the two roads, the U.S. 9th Infantry Division to the north would be cut off from its supplies, and Combat Command B of the 1st Armored Division would be trapped between the 10th Panzer division and its supporting units moving north along the second road. Two battalions of experienced Bersaglieri are recorded by the 23 Field Regiment, Royal Artillery as having made a daylight counterattack through the Ousseltia Plain, but the attack was broken up by heavy British artillery fire.[11] That night, a polyglot collection of British, French, and U.S. forces freed from the line to the north, known as "Nickforce", were sent piecemeal into the lines at Thala. The entire divisional artillery of the U.S. 9th Infantry Division, 48 guns strong, that had started moving on February 17 from their positions 800 miles (1,300 km) west in Morocco, was emplaced that night. When the battle reopened the next day, the defenses were much stronger; the front line was held largely by British infantry with exceptionally strong backing by U.S. and British artillery.[nb 3] When General Kenneth Anderson ordered the 9th and its organic artillery support to Le Kef to meet an expected German attack, U.S. General Ernest N. Harmon (who had been sent by Eisenhower to observe and report on the battle situation and the Allied command) partially countermanded the order, instructing the 9th's artillery commander to stay where he was.[13] On the morning of February 22, an intense artillery barrage from the massed Allied guns pre-empted the planned attack by 10th Panzer, destroying armour and vehicles and disrupting communications. Von Broich, the force commander decided, with Rommel's agreement, to pause and regroup, so giving up the initiative while Allied reinforcements continued to arrive.[14][15] Under constant fire, the 10th was unable to even retire from the field until the onset of darkness.[15]

Overextended and undersupplied, Rommel decided to end the offensive. Fearing that the approaching British Eighth Army would be able to break through the Mareth Line unless it was reinforced, he disengaged and started to withdraw east. On February 23, a massive U.S. air attack on the pass hastened the German retreat, and by the end of February 25, the pass had been reoccupied.

Related actions

The attack by 21st Panzer Division up to Sbiba was stopped on February 19 by elements of the British 1st Infantry Brigade (Guards), the 2nd Battalion Coldstream Guards

German views of the battle

After the battle, both sides studied the results. Rommel was largely contemptuous of both the U.S. equipment and fighting ability and considered them a non-threat. He did, however, single out a few U.S. units for praise, such as the 2nd Battalion, 13th Armored Regiment of Orlando Ward's 1st Armored Division. He characterized this unit's defense of Sbeitla "clever and well fought."[16] For some time after the battle, German units deployed large numbers of captured U.S. vehicles.

Allied views of the battle

Training and tactical failures

The Allies equally seriously studied the results. Positioned by senior commanders who had not personally reconnoitered the ground, U.S. forces were often located too far from each other for mutual support. It was also noted that American soldiers tended to become careless about digging in, exposing their positions, bunching in groups when in open view of enemy artillery observers, and positioning units on topographic crests, where their silhouettes made them perfect targets. Too many soldiers, exasperated by the rocky soil of Tunisia, were still digging shallow slit trenches instead of deep foxholes.[17] The 1st Armored had also apparently not learned lessons from British forces on the receiving end of German anti-tank and screening tactics, though others in the U.S. Army were well aware of the deception.[18] The Allies had also allowed the Germans to attain air superiority over the battlefield, largely preventing effective Allied air reconnaissance and allowing relentless German bombing and strafing attacks that disrupted Allied attempts at deployment and organization. Attacks by the Luftwaffe in close support of German ground offensives often neutralized American attempts to organize effective defensive artillery fire.

Allied command failures

General Dwight D. Eisenhower began restructuring the Allied command, creating a new headquarters (18th Army Group, under General Sir Harold Alexander), to tighten the operational control of the corps and armies of the three Allied nations involved and improve their coordination (there having been significant friction during the previous month's operations).

Most importantly for U.S. Army forces, the II Corps commander, Lloyd Fredendall, was relieved by General Eisenhower and sent to a training command assignment for the remainder of the war. However, the widespread custom of theater commanders to transfer senior commanders who had failed in battlefield assignments to stateside training commands did not in any way improve the reputation or morale of the latter. Instead of receiving a competent leader, those commands would now be saddled with the difficult job of convincing a disgraced commander to take the lead in advocating radical improvements in existing Army training programs - programs which, like Fredendall himself, had contributed to the embarrassing U.S. Army reverses in North Africa.[19]

Eisenhower confirmed through Major General Omar N. Bradley and others that Fredendall's subordinates had no confidence in him as their commander; British General Harold Alexander diplomatically told U.S. commanders, "I'm sure you must have better men than that".[20][21]

While the lion's share of the blame fell on Fredendall, General Anderson—as overall commander of British, French, and American forces—bore at least partial responsibility for the failure to concentrate Allied armored units and integrate forces, which Generals Harmon, Ward, and Alexander noted had disintegrated into a piecemeal collection of disjointed units and commands.[22][nb 4] When General Fredendall disclaimed all responsibility for the poorly-equipped French XIX Corps and denied French requests for support, notably when under pressure at Faïd, Anderson allowed the request to go unfulfilled. Anderson also came in for criticism for calling on the three combat commands of U.S. 1st Armored Division for independent tasking (over the vehement objections of its commander, General Orlando Ward) thus diluting the division's potential effectiveness.[23]

New leadership

On March 6, Major General George S. Patton was placed in command of II Corps, with the explicit task of improving performance. He normally worked directly with Anderson's superior, General Harold Alexander. Bradley was appointed assistant Corps Commander and eventually commanded II Corps. General Fredendall was reassigned stateside, and several other commanders were removed or promoted 'out of the way'. Unlike Fredendall, Patton was a 'hands-on' general not known for hesitancy, and did not bother to request permission when taking action to support his own command or that of other units requesting assistance.[nb 5]

Brigadier General Stafford LeRoy Irwin, who had so effectively commanded the 9th Division's artillery at Kasserine, became a successful divisional commander, along with Cameron Nicholson (later Major-General Sir Cameron Nicholson KBE, CBE, CB, DSO, MC) of Nickforce fame. Commanders were given greater latitude to use their own initiative, to keep their forces concentrated, and to make on-the-spot decisions without first requesting permission by higher command. They were also urged to lead their units from the front, and to keep command posts well forward (Fredendall had built an elaborate, fortified 'bunker' headquarters 70 miles behind the front, and only rarely emerged to visit the lines). The 1st Armored's Orlando Ward, who had become increasingly cautious after Kasserine, was eventually replaced by General Patton with General Harmon.

Tactical and doctrinal changes

Efforts were made to improve massed on-call artillery and air support, which had previously been difficult to coordinate. While U.S. on-call artillery practices improved dramatically, the problem of coordinating close air support was not satisfactorily resolved until the Battle of Normandy over a year later. American air defense artillery also began the process of making substantial doctrinal changes. They had learned that while Stuka dive bombers were vulnerable to .50-caliber anti-aircraft machine gun fire, maneuver units and field artillery in particular needed protection from aerial attack. (In one division, 95% of the air attacks were concentrated on its artillery units.)[25]

Emphasis was also placed on keeping units together, rather than assigning elements of each division to separate tasks as Fredendall had done. II Corps immediately began employing its divisions as cohesive units, rather than parceling out small units on widely separated missions. By the time they arrived in Sicily, their forces were considerably stronger.

In fiction

- The Story of G.I. Joe depicts the battle as the first engagement war correspondent Ernie Pyle witnesses firsthand.

- The Brotherhood of War series by W.E.B. Griffin, starts with an American officer captured at the Battle of the Kasserine Pass.

- The 1970 film Patton begins with a depiction of General Omar Bradley viewing the aftermath of the Battle of the Kasserine Pass.

- The 1980 film The Big Red One depicts the Battle of Kasserine Pass as the first major engagement of the main characters.

- In the videogames Medal of Honor: Allied Assault and Call of Duty 2: Big Red One, the player participates in the Battle of the Kasserine Pass. In the real-time-strategy game Empires: Dawn of the Modern World, the player takes command of the American forces in the Battle of the Kasserine Pass.

- In the novel The Rising Tide by Jeff Shaara

- The battle is briefly mentioned in the 1998 film Saving Private Ryan by Sergent Horbath in Newville, while reminiscing about serving with Captain Miller at Kasserine Pass.

See also

- List of World War II Battles

- North African Campaign timeline

Notes

- Footnotes

- ↑ Poorly equipped and supplied with World War I era light artillery and ammunition, including outmoded shrapnel rounds, the French were nonetheless expert artillerymen and occasionally hammered German patrols and infantry attempting to negotiating the narrow passes.[2]

- ↑ von Arnim had been told to detach the whole division but controversially only released a battlegroup under Felix von Broich, keeping half the division, including its Tiger tank unit for his own purposes[8]

- ↑ There were also 36 British artillery pieces.[12] There was also support from the Derbyshire Yeomanry and the 17th/21st Lancers (both armoured regiments) which gained the Battle Honours of Thala and Kasserine.

- ↑ Harmon reported that General Ward was "hopping mad" at Anderson for dispersing his division, and at Fredendall for allowing Anderson to get away with it.[19]

- ↑ During the advance from Gafsa, General Alexander had given detailed orders to Patton, afterwards changing II Corps' mission not once, but several times. Once beyond Maknassy, Alexander again gave orders Patton considered overly detailed. From then on, Patton simply ignored those parts of mission orders he considered ill-advised on grounds of military expediency and/or a rapidly-evolving tactical situation.[24]

- Citations

- ↑ "Portal Militar y Panzertruppen: Historia de las Fuerzas Armadas alemanas. Kasserine 1943" (in Spanish). Columbia. http://www.europa1939.com/ww2/1943/kasserine.html. Retrieved January 19, 2008.

- ↑ Westrate (1944), pp. 38-39

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Westrate (1944), pp. 109-117

- ↑ Westrate (1944), p. 115

- ↑ Watson (2007), p. 80

- ↑ Watson (2007), pp. 80-81

- ↑ Watson (2007), p. 81

- ↑ Watson (2007), p. 90)

- ↑ Hoffmann (2003), p. 171

- ↑ Murphy in America in WWII Magazine

- ↑ BBC People at War website Accessed November 25, 2007

- ↑ Watson (2007), p. 104

- ↑ Murray, Brian J., Facing The Fox, America in World War II, (April 2006), pp. 28-35

- ↑ Watson (2007), pp. 104 & 105

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Murray, pp. 28-35

- ↑ Zaloga (2005),

- ↑ Westrate (1944), pp. 91-92

- ↑ Westrate (1944), p. 110

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Ossad, Steven L., Command Failures: Lessons Learned from Lloyd R. Fredendall, Army Magazine, March 2003

- ↑ D'Este, Carlo, Eisenhower: A Soldier's Life, Orion Publishing Group Ltd. (2003), ISBN 0-304-36658-7, 0304366587

- ↑ Murray, Brian J. Facing The Fox, America in World War II, (April 2006)

- ↑ Calhoun (2003), pp. 27, 69-70, 83-85

- ↑ Calhoun (2003), pp. 73-75

- ↑ Atkinson (2002), p. 435

- ↑ Hamilton (2005), p. 42

References

- Anderson, Charles R. (1993). Tunisia November 17, 1942 to May 13, 1943. U.S. ARmy Campaigns of WWII. United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 72-12. ISBN 0-16-038106-1. http://www.history.army.mil/brochures/tunisia/tunisia.htm.

- Anderson, Lt.-General Kenneth (1946). Official despatch by Kenneth Anderson, GOC-in-C First Army covering events in NW Africa, November 8, 1942–May 13, 1943 published in London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 37779, p. 5449, November 5, 1946. Retrieved April 23, 2008.

- Atkinson, Rick (2002). An Army at Dawn. New York: Holt. ISBN 0-8050-6288-2.

- Blumenson, Martin (1966). Kasserine Pass. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 3947767.

- Calhoun, Mark T. (2003). Defeat at Kasserine: American Armor Doctrine, Training, and Battle Command in Northwest Africa, World War II. Ft. Leavenworth, KS: Army Command and General Staff College.

- Hamilton, John. "Kasserine Pass". Air Defense Artillery journal (April–June 2005). http://www.airdefenseartillery.com/online/ADA%20In%20Action/WWII/WWII/Kasserine.pdf.

- Hoffmann, Peter (2003). Stauffenberg: A Family History, 1905-1944. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 0773525955.

- Howe, George F. (1957). Northwest Africa: Seizing the Initiative in the West. United States Army Center of Military History.

- Murphy, Brian John. "Facing the Fox". America in WWII Magazine (April 2006). http://www.americainwwii.com/stories/facingthefox.htm. Retrieved December 23, 2007.

- Semmens, Paul. "THE HAMMER OF HELL: The Coming of Age of Antiaircraft Artillery in WW II". Air Defense Artillery Magazine.

- Watson, Bruce Allen (2007) [1999]. Exit Rommel: The Tunisian Campaign, 1942-43. Stackpole Military History Series. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-3381-6.

- Westrate, Edwin V. (1944). Forward Observer. Philadelphia: Blakiston. OCLC 13163146.

- Zaloga, Steven (2005). Kasserine Pass 1943 - Rommel's Last Victory. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-914-2.

External links

- Facing The Fox In The Kasserine Pass

- Entry in the Leaders & Battles Database

- Kasserine Pass Battles: Staff Rides Background Materials - Collection Primary Sources and Analysis of the Battle compiled by the United States Army Center of Military History